All We Are Is Light Made Solid - A Day in Paris

10 November 1987-Paris, France

"Simple shapes are inhuman: they fail to resonate with the way nature organizes itself or with the way human perception sees the world."

— George Zebrowsik

8:20am

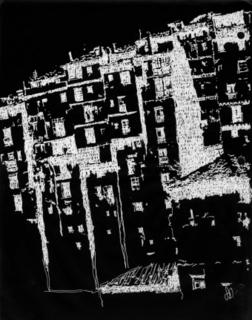

It is an October morning, still only 7:30, on Rue de la Harpe. I pull back the curtains and open the window (closed for quiet during the night) and a clamor of noise from the street confuses the clean light that slices into my room. It is a market day in the Quarter and just across the way is a miniature Halle or public market, where towering masses of fruits and grains are grouped with painterly effect. The crisp air and the slippery smell of the urban ground, still wet from the morning street cleaners, give substance to the flickering events below. Details, so many details: they are of what experiences are made. And such morning scenes are always thick with them, a tapestry of every color woven in unexpected ways. Yet such chaos is always so instantly coherent to the eye, such complexity is always so tangible to the senses. Even all of those hucksters and small potâger peddlers thronging into the Quarter with their chauffeuring wives are given essence by the noisy Babel they produce, one that would last until half past noon, when the market will suddenly quiet down and vanish not unlike how entire eras vanish, rhythmically, leaving just an impression behind.

I arrived in Paris three months ago. I cannot believe it has been 10 months since I ran away from home. And after traveling to Perugia and Siena of central Italy, I have come here. Why? Did I not discover in Italy what I wanted to discover about myself? I was captured by the Tuscan urgency for life, the same raw and unadulterated tactility that persuaded Degas to visit Italy so many times. Yet, months later, I left Siena for Paris in pursuit of romance. And as in Italy, I found that life here in Paris is too intense to just walk away from it; doing so would be to create a rift between living and merely being alive, and so it has become not so much a matter of wanting to leave this place as it is a matter of being able to conceive of it. Yes, I will be here a long time indeed.

3:18pm

“Bonjour, Monsieur!”

It was my friend Jérôme, who came to ask if I wanted déjeûner. Always Jérôme comes to ask this question, “Veut-il le petit déjeûner ce matin?” He visits me for this purpose and almost no other. I sent down a friendly wave in reply and brought myself down the stairs.

“Ça va, Jérôme?”

“Bien, merci. Aujourd’hui est très beau, non?”

“Oui, est trés beau.”

A good guy Jérôme, a man of over forty and still so curious about the world. He has no small share of the bright intelligence which surprises one among les petit bourgeois, the “little people” or humble class of Paris as they were called. It is a race gift, I think. Unlike people of similar classes in other countries, I venture to hold firm that the French people, especially of Paris, possess a degree of genius unknown to any other nation. I would define it specifically as the veraciousness of common sense.

“How do you say in Italian that the day is nice?” he asked.

“Actually, Italians don’t say that the day is nice,” I explained. “They say ‘Fa bello oggi,’ using the verb fare, which means to make. To say ‘Fa bello’ is actually to say that the day literally makes beauty. You see, even simple utterances in Italian are almost poetic. All of its dialects are this way. To speak is to realize and express the subtle nuances of life. Much like how you Parisians live here in the Quarter, or how French painters like Passarro and Degas used their brushes one-hundred years ago and less.”

Jérôme smiled in acceptance and motioned me in the direction of our favorite pastry shop, Sud Tunisien, just a few minutes walk away.

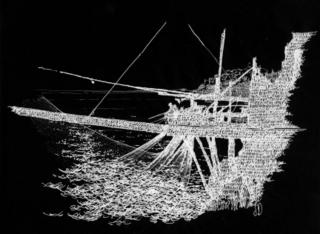

We turned up Rue de la Harpe, and weaved ourselves into the market on our way towards the river Seine. This was one of the great streets of Paris from Roman times until the last part of the nineteenth century. Though now closed to traffic, Jérôme told me that from its earliest days this street was once an important roadway of the Roman Empire. It wound its serpentine course from the Seine down towards the south of France and that at least fourteen names for it have since been recorded, like the Guitarist and even, says Jérôme, the Old Buckler. It is now called the street of the Harp Player, after King David, but most people around here still refer to it by the name of a favorite café or by the names of their friends who live in one of its apartments. I call it Prégrille, after the French restaurant on the corner. It seems in all of this that Rue de la Harpe is a temporal anomaly, defying time and history much like how light defies form. For me, however, walking down these cobblestones was to walk along thousands of years of human endeavors and aspirations, the blood of history. Either way, perhaps one thing is certain: that we are a moment in astronomic time, a transient of the earth. Only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a few pages of scant conclusions. I proceed.

We visited a street vendor and looked at the various goods. On the table were a display rack of impossible postcards, piles of T-shirts with advertisements, and an array of aluminum-cast Eiffel Towers. Jérôme nodded towards several framed, full-size posters of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings leaning against the tables, works by Monet and Van Gogh mostly. We looked at the Monet’s together.

“And what of Monet, how would you say a man like that lived?” he asked me.

“Hm, with life and vigor, I suppose. I really don’t know. I only know that I see posters of his paintings more so than the other French artists in every gift shop window and touristy vendor like this one.”

“Every area of color is like your utterance of life,” Jérôme explained. “Every subject is fleeting and spontaneous. But look at the details, too,” he whispered. “Little of anything on their own, aren’t they? Yet each one seems like a tiny subject in itself, within the whole subject. In these works, Monet looked at fragments, close-up, and transformed their scale with his large brush and his way of thinking about the canvas, light, form, and color. Details make the picture, but take them away, and they reduce the mood. In themselves they seem insignificant, and when you step back you can see that that is true, that they are not as important in rendering the whole effect as are their actual relationships to one another.”

“I know that he painted quickly, with urgency,” I added, “pursuing the fleeting impression of things.”

“Monet understood a lot of things that modern science has only recently discovered. It was da Vinci before him who wrote that the eye is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the world, and Monet certainly took advantage of this precious tool. And as for my part in life,” he laughed and he began our walk again, “I understand only that all our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike—and yet it is now the most precise thing we have.

“Chaos,” he announced, and he pointed to a lit candle on the table of another vendor. “It appears to be a very simple system—a wick, the wax—yet it’s inherently unpredictable. The best computer in the world could not predict the pattern this light will take from moment to moment. It’s the secret of the universe.”

“Sounds messy,” I said with a smile.

“Yes,” and he gazed back at the posters. “But what a beautiful mess it can be. It’s what makes the universe so full of possibilities, gives us what free will we have, or at least lets us think that we have it. But tell me, now,” and he hesitated, as if to add drama to what he wanted to ask, “when was the last time you sat to watch the sun rise and felt the spin of the earth?”

“The spin of the earth?”

“Yes, the movement of the planet. It rockets through space at 240.000 kilometers per second. The solar system and the galaxy spin faster than what our best technology can measure. And yet we walk along this street and feel nothing of it. It’s all part of the secret of the universe and this man Monet must have felt it, he must have known it.”

To hear Jérôme talk this way only made my mind wander a moment towards other things, though not far from what he was saying. For instance, I heard rumors that Monet also loved this particular street and that he would often visit it when in the Quarter, especially on those days enshrouded by rain and mist. During his walks I’m told that girls sang from the seventh floor of their apartments at the army men wandering around below and the whole street was an anthill for Parisian students and artists and musicians, all forming a creature of a thousand legs from one end of the course to the other. Looking down at the ground I could only try to imagine the scene for Monet. But the street was miles away from anything I could know so well. The profoundest distances, after all, are never geographical.

“Perhaps he felt gravity,” I tried. “We’re reminded of it daily. But why ask me? It’s you who studies the history of science and painting, not I.”

“Gravity?” Jérôme smirked the kind of smirk that informs others of their obvious idiocy. Having done so, he proceeded to verify his claim.

“At the beginning of this century,” he began, “Rachmaninoff wrote his second symphony and it was powerful. It still is for some people. But today, is there no department store elevator or luxury car commercial that does not use some version of his Symphony No. 2, or his Piano Concerto No. 2, or Tchaikovsky, or Mozart, or Vavaldi? It’s still there, being played in the background, used to sell products, and it adds to the mood, but people are rarely aware of its poetic impact. The thing of it is, when human sensations are replaced by media’s narratives the earth doesn’t need to spin any more. Media exists outside the laws of gravity. Its force lies within the power of the image and its ability to produce some virtual gravity of its own. Look at that there, of Monet’s Water Lilies. There is why I ask you.”

“I don’t see your point.”

“That, I’m afraid, is my point.”

Despite his intelligence Jérôme could be rather confusing, I confess. In most friendships, there is one who is more managing than the other, one who is more outgoing, or more commanding so that, in short, he produces a kind of comfort in a friendship to which even the less dominate person is content. With Jérôme however, if I began to feel the polarity, or if I notice the submissive role in which I am left floundering, he would spontaneously say something that entirely confuses mainly himself and then would proceed to fabricate some fantastic story that only makes him out to be a little neurotic. He is almost uneasy in this way: intimidating, then neurotic. I don’t know which is better.

I should also confess that it was Jérôme who told me the rumor about Monet’s love of this street, which now seems highly suspicious. But one thing I have learned from Jérôme is that what matters in the world is not so much what is true as what is entertaining, at least so long as the truth is unknowable.

We continued up the street, and Jérôme continued to entertain me.

“In Russia, where he was thought to be the next Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff was not unlike Monet. He wrote his second symphony in 1907 and by that time Monet had already become obsessed by the water lily motif, having painted many of them, and his Les Grande Décorations was yet to come. During their last decades, both men had similar inspirations. The town of Inånovka, a place of tranquility and family, became synonymous with Rachmaninoff’s later compositions, as was Monet’s garden to his own work. And they were getting older yet becoming more impressive. For Rachmaninoff, though world famous, it was his creative comeback from his poorly received first symphony; and Monet, already famous and wealthy, now faced the issues of blindness and old age with new life. Both were creating symphonies in imaginative designs, packed with expressive melodies, restoring confidence to their careers. I can’t think of a better comparison of two sets of art objects about time, the Waterlilies Suite and Symphony No. 2 in E Minor. Music and painting, even sculpture and literature, were almost merging at that time; but then came the calamities of two world wars, both of which served to splinter the courses of the arts. And now that poster, and all of these advertisements, are the wandering ghosts of Rachmaninoff, Monet and others in a world grown alien to them.”

“Two pieces about time?” I wondered loud.

We reached Sud Tunisien. Before receiving an answer to my question, we bought our breakfasts, which never varied from a sweet role, café au lait, and if available fresh, a handful of grapes. We sat ourselves as always on the street curb just outside the pastry entrance. Jérôme hummed a tune, something French and as clamorous as the market itself. It all fit in however.

“If we wished to make a new world,” he said through his sweet role while looking out into the crowd, “we have the material already. The first one, too, was made out of chaos. That is the character of Monet’s world.”

I just listened.

“I used to think that the moment was a fleeting thing—here in a wink, gone in a wink, with all of its infinite possibilities played out between two instances of nothing, between which laid the experience of life. That’s music. It is something we experience through time, something moving and intoxicating. We find understanding in music from the relationship of its notes, one moment followed by the next, leaving a gap in between them. Then I look at the little water lilies of Monet, or I walk around the huge oval rooms of his Grande Décorations, and I see that, yes, the moment is an instance, just flickers of chaotic light, but it can also eclipse history itself. Monet gives us what is between the musical notes, between one flicker of light and the next. His are not just oil paintings made by a half-blind old man. Each painting is a symphony of light made solid, freeze-framed in a time where there are no seasons and no objects.”

By noon the market was already closing down. The framers loaded their trucks with empty baskets and the vendors urged on the last few potential buyers. So quickly the entire street looked different, even felt different; yet I wandered back to my apartment alone in thought about the entire morning as if I were in the same moment. I thought about Jérôme and I thought about how easily he can create a new way of seeing the world out of insignificant little facts that have big relationships to each other. He’s a lot like Monet, I decide, realizing life as he lived it.

And then I wondered about how this could be done. While looking at buildings and people on Rue de la Harpe I found myself squinting to see the world as impressions of light floating in front of their objects. But it didn’t work, except, when I happened to glance at building No. 33. I suddenly realized it, the secret of the universe. Remember that this street was once called the Old Buckler. Well, I found it; the name, I mean. It is written inside the sculpted stone frame of a doorway. A little thing in itself, I know, but just then I realized that life itself is the movement from the forgotten little things into the unexpected big things, and I believe that that, if nothing else, is certainly true.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

(This post is also on my Art blog, Wasting Time as Art.)

"Simple shapes are inhuman: they fail to resonate with the way nature organizes itself or with the way human perception sees the world."

— George Zebrowsik

8:20am

It is an October morning, still only 7:30, on Rue de la Harpe. I pull back the curtains and open the window (closed for quiet during the night) and a clamor of noise from the street confuses the clean light that slices into my room. It is a market day in the Quarter and just across the way is a miniature Halle or public market, where towering masses of fruits and grains are grouped with painterly effect. The crisp air and the slippery smell of the urban ground, still wet from the morning street cleaners, give substance to the flickering events below. Details, so many details: they are of what experiences are made. And such morning scenes are always thick with them, a tapestry of every color woven in unexpected ways. Yet such chaos is always so instantly coherent to the eye, such complexity is always so tangible to the senses. Even all of those hucksters and small potâger peddlers thronging into the Quarter with their chauffeuring wives are given essence by the noisy Babel they produce, one that would last until half past noon, when the market will suddenly quiet down and vanish not unlike how entire eras vanish, rhythmically, leaving just an impression behind.

I arrived in Paris three months ago. I cannot believe it has been 10 months since I ran away from home. And after traveling to Perugia and Siena of central Italy, I have come here. Why? Did I not discover in Italy what I wanted to discover about myself? I was captured by the Tuscan urgency for life, the same raw and unadulterated tactility that persuaded Degas to visit Italy so many times. Yet, months later, I left Siena for Paris in pursuit of romance. And as in Italy, I found that life here in Paris is too intense to just walk away from it; doing so would be to create a rift between living and merely being alive, and so it has become not so much a matter of wanting to leave this place as it is a matter of being able to conceive of it. Yes, I will be here a long time indeed.

3:18pm

“Bonjour, Monsieur!”

It was my friend Jérôme, who came to ask if I wanted déjeûner. Always Jérôme comes to ask this question, “Veut-il le petit déjeûner ce matin?” He visits me for this purpose and almost no other. I sent down a friendly wave in reply and brought myself down the stairs.

“Ça va, Jérôme?”

“Bien, merci. Aujourd’hui est très beau, non?”

“Oui, est trés beau.”

A good guy Jérôme, a man of over forty and still so curious about the world. He has no small share of the bright intelligence which surprises one among les petit bourgeois, the “little people” or humble class of Paris as they were called. It is a race gift, I think. Unlike people of similar classes in other countries, I venture to hold firm that the French people, especially of Paris, possess a degree of genius unknown to any other nation. I would define it specifically as the veraciousness of common sense.

“How do you say in Italian that the day is nice?” he asked.

“Actually, Italians don’t say that the day is nice,” I explained. “They say ‘Fa bello oggi,’ using the verb fare, which means to make. To say ‘Fa bello’ is actually to say that the day literally makes beauty. You see, even simple utterances in Italian are almost poetic. All of its dialects are this way. To speak is to realize and express the subtle nuances of life. Much like how you Parisians live here in the Quarter, or how French painters like Passarro and Degas used their brushes one-hundred years ago and less.”

Jérôme smiled in acceptance and motioned me in the direction of our favorite pastry shop, Sud Tunisien, just a few minutes walk away.

We turned up Rue de la Harpe, and weaved ourselves into the market on our way towards the river Seine. This was one of the great streets of Paris from Roman times until the last part of the nineteenth century. Though now closed to traffic, Jérôme told me that from its earliest days this street was once an important roadway of the Roman Empire. It wound its serpentine course from the Seine down towards the south of France and that at least fourteen names for it have since been recorded, like the Guitarist and even, says Jérôme, the Old Buckler. It is now called the street of the Harp Player, after King David, but most people around here still refer to it by the name of a favorite café or by the names of their friends who live in one of its apartments. I call it Prégrille, after the French restaurant on the corner. It seems in all of this that Rue de la Harpe is a temporal anomaly, defying time and history much like how light defies form. For me, however, walking down these cobblestones was to walk along thousands of years of human endeavors and aspirations, the blood of history. Either way, perhaps one thing is certain: that we are a moment in astronomic time, a transient of the earth. Only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a few pages of scant conclusions. I proceed.

We visited a street vendor and looked at the various goods. On the table were a display rack of impossible postcards, piles of T-shirts with advertisements, and an array of aluminum-cast Eiffel Towers. Jérôme nodded towards several framed, full-size posters of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings leaning against the tables, works by Monet and Van Gogh mostly. We looked at the Monet’s together.

“And what of Monet, how would you say a man like that lived?” he asked me.

“Hm, with life and vigor, I suppose. I really don’t know. I only know that I see posters of his paintings more so than the other French artists in every gift shop window and touristy vendor like this one.”

“Every area of color is like your utterance of life,” Jérôme explained. “Every subject is fleeting and spontaneous. But look at the details, too,” he whispered. “Little of anything on their own, aren’t they? Yet each one seems like a tiny subject in itself, within the whole subject. In these works, Monet looked at fragments, close-up, and transformed their scale with his large brush and his way of thinking about the canvas, light, form, and color. Details make the picture, but take them away, and they reduce the mood. In themselves they seem insignificant, and when you step back you can see that that is true, that they are not as important in rendering the whole effect as are their actual relationships to one another.”

“I know that he painted quickly, with urgency,” I added, “pursuing the fleeting impression of things.”

“Monet understood a lot of things that modern science has only recently discovered. It was da Vinci before him who wrote that the eye is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the world, and Monet certainly took advantage of this precious tool. And as for my part in life,” he laughed and he began our walk again, “I understand only that all our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike—and yet it is now the most precise thing we have.

“Chaos,” he announced, and he pointed to a lit candle on the table of another vendor. “It appears to be a very simple system—a wick, the wax—yet it’s inherently unpredictable. The best computer in the world could not predict the pattern this light will take from moment to moment. It’s the secret of the universe.”

“Sounds messy,” I said with a smile.

“Yes,” and he gazed back at the posters. “But what a beautiful mess it can be. It’s what makes the universe so full of possibilities, gives us what free will we have, or at least lets us think that we have it. But tell me, now,” and he hesitated, as if to add drama to what he wanted to ask, “when was the last time you sat to watch the sun rise and felt the spin of the earth?”

“The spin of the earth?”

“Yes, the movement of the planet. It rockets through space at 240.000 kilometers per second. The solar system and the galaxy spin faster than what our best technology can measure. And yet we walk along this street and feel nothing of it. It’s all part of the secret of the universe and this man Monet must have felt it, he must have known it.”

To hear Jérôme talk this way only made my mind wander a moment towards other things, though not far from what he was saying. For instance, I heard rumors that Monet also loved this particular street and that he would often visit it when in the Quarter, especially on those days enshrouded by rain and mist. During his walks I’m told that girls sang from the seventh floor of their apartments at the army men wandering around below and the whole street was an anthill for Parisian students and artists and musicians, all forming a creature of a thousand legs from one end of the course to the other. Looking down at the ground I could only try to imagine the scene for Monet. But the street was miles away from anything I could know so well. The profoundest distances, after all, are never geographical.

“Perhaps he felt gravity,” I tried. “We’re reminded of it daily. But why ask me? It’s you who studies the history of science and painting, not I.”

“Gravity?” Jérôme smirked the kind of smirk that informs others of their obvious idiocy. Having done so, he proceeded to verify his claim.

“At the beginning of this century,” he began, “Rachmaninoff wrote his second symphony and it was powerful. It still is for some people. But today, is there no department store elevator or luxury car commercial that does not use some version of his Symphony No. 2, or his Piano Concerto No. 2, or Tchaikovsky, or Mozart, or Vavaldi? It’s still there, being played in the background, used to sell products, and it adds to the mood, but people are rarely aware of its poetic impact. The thing of it is, when human sensations are replaced by media’s narratives the earth doesn’t need to spin any more. Media exists outside the laws of gravity. Its force lies within the power of the image and its ability to produce some virtual gravity of its own. Look at that there, of Monet’s Water Lilies. There is why I ask you.”

“I don’t see your point.”

“That, I’m afraid, is my point.”

Despite his intelligence Jérôme could be rather confusing, I confess. In most friendships, there is one who is more managing than the other, one who is more outgoing, or more commanding so that, in short, he produces a kind of comfort in a friendship to which even the less dominate person is content. With Jérôme however, if I began to feel the polarity, or if I notice the submissive role in which I am left floundering, he would spontaneously say something that entirely confuses mainly himself and then would proceed to fabricate some fantastic story that only makes him out to be a little neurotic. He is almost uneasy in this way: intimidating, then neurotic. I don’t know which is better.

I should also confess that it was Jérôme who told me the rumor about Monet’s love of this street, which now seems highly suspicious. But one thing I have learned from Jérôme is that what matters in the world is not so much what is true as what is entertaining, at least so long as the truth is unknowable.

We continued up the street, and Jérôme continued to entertain me.

“In Russia, where he was thought to be the next Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff was not unlike Monet. He wrote his second symphony in 1907 and by that time Monet had already become obsessed by the water lily motif, having painted many of them, and his Les Grande Décorations was yet to come. During their last decades, both men had similar inspirations. The town of Inånovka, a place of tranquility and family, became synonymous with Rachmaninoff’s later compositions, as was Monet’s garden to his own work. And they were getting older yet becoming more impressive. For Rachmaninoff, though world famous, it was his creative comeback from his poorly received first symphony; and Monet, already famous and wealthy, now faced the issues of blindness and old age with new life. Both were creating symphonies in imaginative designs, packed with expressive melodies, restoring confidence to their careers. I can’t think of a better comparison of two sets of art objects about time, the Waterlilies Suite and Symphony No. 2 in E Minor. Music and painting, even sculpture and literature, were almost merging at that time; but then came the calamities of two world wars, both of which served to splinter the courses of the arts. And now that poster, and all of these advertisements, are the wandering ghosts of Rachmaninoff, Monet and others in a world grown alien to them.”

“Two pieces about time?” I wondered loud.

We reached Sud Tunisien. Before receiving an answer to my question, we bought our breakfasts, which never varied from a sweet role, café au lait, and if available fresh, a handful of grapes. We sat ourselves as always on the street curb just outside the pastry entrance. Jérôme hummed a tune, something French and as clamorous as the market itself. It all fit in however.

“If we wished to make a new world,” he said through his sweet role while looking out into the crowd, “we have the material already. The first one, too, was made out of chaos. That is the character of Monet’s world.”

I just listened.

“I used to think that the moment was a fleeting thing—here in a wink, gone in a wink, with all of its infinite possibilities played out between two instances of nothing, between which laid the experience of life. That’s music. It is something we experience through time, something moving and intoxicating. We find understanding in music from the relationship of its notes, one moment followed by the next, leaving a gap in between them. Then I look at the little water lilies of Monet, or I walk around the huge oval rooms of his Grande Décorations, and I see that, yes, the moment is an instance, just flickers of chaotic light, but it can also eclipse history itself. Monet gives us what is between the musical notes, between one flicker of light and the next. His are not just oil paintings made by a half-blind old man. Each painting is a symphony of light made solid, freeze-framed in a time where there are no seasons and no objects.”

By noon the market was already closing down. The framers loaded their trucks with empty baskets and the vendors urged on the last few potential buyers. So quickly the entire street looked different, even felt different; yet I wandered back to my apartment alone in thought about the entire morning as if I were in the same moment. I thought about Jérôme and I thought about how easily he can create a new way of seeing the world out of insignificant little facts that have big relationships to each other. He’s a lot like Monet, I decide, realizing life as he lived it.

And then I wondered about how this could be done. While looking at buildings and people on Rue de la Harpe I found myself squinting to see the world as impressions of light floating in front of their objects. But it didn’t work, except, when I happened to glance at building No. 33. I suddenly realized it, the secret of the universe. Remember that this street was once called the Old Buckler. Well, I found it; the name, I mean. It is written inside the sculpted stone frame of a doorway. A little thing in itself, I know, but just then I realized that life itself is the movement from the forgotten little things into the unexpected big things, and I believe that that, if nothing else, is certainly true.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

(This post is also on my Art blog, Wasting Time as Art.)

<< Home