Appoaching Ireland

October 13, 1997-Southern Coast, up to the North

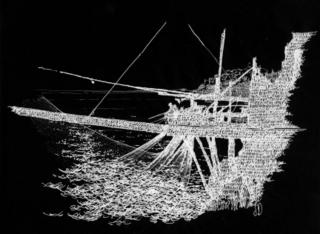

The weather is deceptive. The breeze is so still, like some stratagem laden with devices unknown. As seen through the windows of the ferry, the air is careful of itself, as if at any moment it could move in a precarious way and the pearl-grey sky will tumble down from above.

It is days like this that seem most charged with meaning. In every detail there are messages that want to be defined and conceived in words, but for that very reason they are indecisive. I’m not foolish enough to believe that it is just the Irish in me or that, despite experiences, on such days my thoughts are composed neither from my mind nor from chance, but from a sea and a land so vigorous with meaning that the most common phenomena become semantic infections.

As I approach Ireland, I am watching the rain suffuse the windows, anxiously expecting the ripples running down the glass to reveal a message to me. I am waiting to see if their scripture-like movements will write out a testament to the universe or flash a transmission from some other place. It is a trickery of weather in this place, all trickery that I had not before known. And soon I will be on Ireland’s southern shore, still far from my childhood memories in the north, and I will stand there a moment in the winter rain and I will try to comprehend it all, try to grasp what is too big and too much. I will watch the sky as a trap in waiting for enlightening clouds, a temptation to lure remote and wise winds, offering myself as an ideal relict of the fiery of storms, waiting to be impaled with the meaning of this place.

October 18, 1997

Further north now. Several miles outside the town of Maam Cross there is an old church from medieval times. I came here because I heard stories that this old church was haunted by the headless. The Celts seem to have regarded the human head, and the lack of a head, with particular reverence as the seat of the human spirit. Perhaps the loss of one’s head was the loss of one’s spirit. (It is not surprising, then, that so many carvings of heads can be found throughout Ireland and Britian.)

That idea was rooted in this land. On one on the surviving windows of the church, it is written in Gaelic, “We have lost our land to the caora [sheep]. Here we rest in anger.” During the later medieval times and especially during British rule after the Normandy ascendancy, he wool of sheep became more prosperous to land owners than rent paid by peasants. Many peasants were forced off their land by British land owners and banks, and they found shelter in small churches like this one.

I’ve come back here for the second day and night, but no ghosts have shown themselves.

October 20, 1997

In the west I found that many did not believe in either hell or in ghosts. Hell was an invention of the priests, and ghosts, well, they just wouldn’t be permitted to wander around in that way, “to go trapsin about the e’rth on their own free will.”

But, according to one woman I met in town, “t’ere be faeries, and t’ere be little leprechauns, and fallen angles to see some nights, too.”

In the center of Ireland, where the land is full of green plains and even greener hills, no matter what one doubts, one never doubts the faeries, the children of Lilith, or as everyone here knows “they just stand to reason.” I’m told that if I go to some of the areas near the mountains and if I watch the faeries paths at night, I might see a faery for myself. They are said to travel every evening from the hills to the sea, and from the sea to the hills. Tomorrow, I set out to find a faery of my very own.

October 22, 1997

I’m in the in the middle lowlands near the town of Dunmore East, also near the coast but not so much a coastal town as the traditional towns of fly fishers and cockfights. I asked around about the faeries path, but I was warned. Faeries are something to be avoided. “They can do you good or they can do you harm, so it’s best not to get too close when you seen them.”

I sat on the side of a road in the early evening, reading and waiting for faeries to arrive. I was told that I’d have to be very patient, so I waited a long time. And for a long time, none came. I started think about the way people explain fairy tales and myths—“don’t get too close because they might harm you”—and how myths play such as important role in human existence. But then, finally, the faeries did start to come out, hundreds of them. In a short time, they filled the air around me.

They were moths.

They were moths.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

The weather is deceptive. The breeze is so still, like some stratagem laden with devices unknown. As seen through the windows of the ferry, the air is careful of itself, as if at any moment it could move in a precarious way and the pearl-grey sky will tumble down from above.

It is days like this that seem most charged with meaning. In every detail there are messages that want to be defined and conceived in words, but for that very reason they are indecisive. I’m not foolish enough to believe that it is just the Irish in me or that, despite experiences, on such days my thoughts are composed neither from my mind nor from chance, but from a sea and a land so vigorous with meaning that the most common phenomena become semantic infections.

As I approach Ireland, I am watching the rain suffuse the windows, anxiously expecting the ripples running down the glass to reveal a message to me. I am waiting to see if their scripture-like movements will write out a testament to the universe or flash a transmission from some other place. It is a trickery of weather in this place, all trickery that I had not before known. And soon I will be on Ireland’s southern shore, still far from my childhood memories in the north, and I will stand there a moment in the winter rain and I will try to comprehend it all, try to grasp what is too big and too much. I will watch the sky as a trap in waiting for enlightening clouds, a temptation to lure remote and wise winds, offering myself as an ideal relict of the fiery of storms, waiting to be impaled with the meaning of this place.

October 18, 1997

Further north now. Several miles outside the town of Maam Cross there is an old church from medieval times. I came here because I heard stories that this old church was haunted by the headless. The Celts seem to have regarded the human head, and the lack of a head, with particular reverence as the seat of the human spirit. Perhaps the loss of one’s head was the loss of one’s spirit. (It is not surprising, then, that so many carvings of heads can be found throughout Ireland and Britian.)

That idea was rooted in this land. On one on the surviving windows of the church, it is written in Gaelic, “We have lost our land to the caora [sheep]. Here we rest in anger.” During the later medieval times and especially during British rule after the Normandy ascendancy, he wool of sheep became more prosperous to land owners than rent paid by peasants. Many peasants were forced off their land by British land owners and banks, and they found shelter in small churches like this one.

I’ve come back here for the second day and night, but no ghosts have shown themselves.

October 20, 1997

In the west I found that many did not believe in either hell or in ghosts. Hell was an invention of the priests, and ghosts, well, they just wouldn’t be permitted to wander around in that way, “to go trapsin about the e’rth on their own free will.”

But, according to one woman I met in town, “t’ere be faeries, and t’ere be little leprechauns, and fallen angles to see some nights, too.”

In the center of Ireland, where the land is full of green plains and even greener hills, no matter what one doubts, one never doubts the faeries, the children of Lilith, or as everyone here knows “they just stand to reason.” I’m told that if I go to some of the areas near the mountains and if I watch the faeries paths at night, I might see a faery for myself. They are said to travel every evening from the hills to the sea, and from the sea to the hills. Tomorrow, I set out to find a faery of my very own.

October 22, 1997

I’m in the in the middle lowlands near the town of Dunmore East, also near the coast but not so much a coastal town as the traditional towns of fly fishers and cockfights. I asked around about the faeries path, but I was warned. Faeries are something to be avoided. “They can do you good or they can do you harm, so it’s best not to get too close when you seen them.”

I sat on the side of a road in the early evening, reading and waiting for faeries to arrive. I was told that I’d have to be very patient, so I waited a long time. And for a long time, none came. I started think about the way people explain fairy tales and myths—“don’t get too close because they might harm you”—and how myths play such as important role in human existence. But then, finally, the faeries did start to come out, hundreds of them. In a short time, they filled the air around me.

They were moths.

They were moths.Downs - Copyright © 2005

<< Home